| | | Chronology of the main civilizations

in Syria: |

| Period | Main Center | Syrian Principalities | From | To | | |

Mesolithic

| | Kebarian | Syria | Syrian Levant and Ephrates as separate and small settlments | c. 18000 BC | c. 12000 BC | | Natufian | Syria / Mid Euphrates | Mureibet - Abu Huraira - Jebel Aruda - Yabrud | c. 12000 BC | c. 8000 BC |

Neolithic

| | Hassuna | Iraq | Syrian Jazeera - Sinjar Mountains | c. 8500 BC | c. 5000 BC | | Tell Halaf | Syria / North East on Turkeish border | Tell Halaf - … | c. 6000 BC | c. 4000 BC | | Umuq | Syria / north of Euphrates | Umuq plains - Jubeil Lebanon | c. 6000 BC | c. 4000 BC | | Samurra' | Iraq | Syrian Jazeera (north of Euphrates) | c. 5500 BC | c. 5000 BC | | Ubaid | Iraq | Northern regions in Syria - Syrian Levant | c. 5300 BC | c. 4000 BC |

Ancient History (Bronze & Iron Ages)

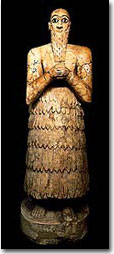

| | Sumerian (Uruk & Ur) | Iraq | Habbuba - Tell Qannas - Jebel Aruda - Mari - Baghuz (Abu Kemal) | c. 4100 BC | c. 2000 BC | | Canaanite (Phoenician) | Syria - Lebanon - Palestine | Syrian Levant - Ugarit - Ebla - Alalakh - Amuru - Damascus - Qadesh | c. 3500 BC | c. 1000 BC | | Elamite | Iran | Northern regions in Syria | c. 2700 BC | 539 BC | | Akkadian | Iraq | Tell Brak - Mari - Ebla - Yamhad (Aleppo) | c. 2450 BC | 2159 BC | | Hurrians | Turkey / Anatolia - Syria / Khabur Valley | Yamhad - Tell Brak - Tell Halaf - Alalakh - Ugarit - Mari | c. 2400 BC | c. 1250 BC | | Babylonian | Iraq | Mari - Ebla - Yamhad - Ugarit | 2159 BC | 1595 BC | | Amorite | Syria | Levant cities - North of Euphrates | c. 2150 BC | c. 1600 BC | | Assyrian | Iraq | Khabur River Valley - Mari - Shubat Enlil - North of Syria | 1920 BC | 612 BC | | Hittite | Turkey / Anatolia | Levant cities - northern cities | c. 1750 BC | 1160 BC | | Mittanite | Syria | Khabur River Valley - Yamhad | c. 1500 BC | c. 1350 BC | | Aramean | Syria | Mari - Ugarit - Damascus - Maalula | c. 1450 BC | Present day | | Roman | Italy / Rome | Levant cities - Bosra - Palmyra - Damascus - Apamea | 753 BC | 476 AD | | Chaldean | Syria | Southern Mesopotamia (north east of Euphrates) | 612 BC | 539 BC | | Persian | Iran | Mari - Ebla - Yamhad - Aleppo - Damascus | 550 BC | 651 AD | | Hellenisntic | Greece | Levant cities - Amrit - Arwad - Aleppo - Damascus | 333 BC | c. 30 BC |

Middle Ages

| | Byzantine | Turkey / Antioch | Levant cities - Aleppo - Homs - Syrian Jazeera | 330 AD | 1453 AD | | Islam | Saudi Arabia / Mecca - Medina | | 632 AD | | Ummayyad | Syria / Damascus | | 661 AD | 750 AD | | Abbasid | Iraq / Baghdad | | 750 AD | 1258 AD |

Islamic Era / The Arab States

| | Hamdanid | Iraq - Syria | Aleppo and northern area | 890 AD | 1004 AD | | Fatimid | Tunis / Mahdia (909 - 969) - Egypt / Cairo | Damascus - Aleppo - Hama - Homs | 909 AD | 1171 AD | | Ikhshidid | Egypt / Cairo | Damascus - Aleppo - Hama - Homs | 935 AD | 969 AD | | Seljuq / Saljuk | Turkey | Aleppo and northern area | 1055 AD | 1128 AD | | Crusaders | Christian Europe / in the name of Catholic Church | Syrian cities and castles [Castle Blanc/Safit - Krak Des Chevalliers

- Marqab Caslte] | 1095 AD | 1187 AD | | Ayyubid | Kurdistan by orgin - Egypt | Damascus - Aleppo - Hama - Homs | 1171 AD | 1263 AD | | Mameluke | Egypt (Slaves from Turkey) | Damascus - Aleppo - Hama - Homs | 1250 AD | 1517 AD | | Ottoman | Turkey / Edrin - Istanbul | Different Syrian cities | 1299 / in Syria 1516 AD | 1920 / 1922 Ottoman's collapse AD | | French Mandate | | | 1920 AD | 1946 AD | | Syrian Arab Republic | | | 1946 AD | present day | | top | | |

Syria occupies a strategic position of

incomparable value. It bears the traces of

many caravan routes, Roman roads, pilgrimage

trails and superhighways that testify to its

role as a corridor for east/west trade. Through Roman and Byzantine times Syria

became the focal point in efforts to

maintain a universal empire. To the east,

Euphrates is the highway into Mesopotamia

that has never bothered potential

aggressors. To the southeast, the Great

Arabian Dessert has historical funneled its

excess energies in the direction of Syria,

causing population changes that have marked

several of its major historical eras. The

northern plains have likewise been a magnet

for the disaffected, marginalized by

successive changes in Turkey. But beyond the natural chokepoint in the

north west, Syria is an open land without

doors. It learned to survive on its wits -

by trading and statecraft rather than

closing itself off as a fortress land. It

has learnt to transmit rather than to block

- to absorb the first ethnic waves from the

steppes and desert to the south; to pass on

the great themes and ideas that have moved

between east and west; to provide a footing

between the religious currents that have

swept the region. Settling, Agriculture and

the Beginning of civilization 9000BC: This is where civilization began. The

development of agriculture in Syria meant

settled communities. Tribes and peoples

began to prefer agriculture to hunting and

with the appearance of bronze and copper

tools, agriculture developed quickly. Along

with the development in agriculture came a

development in trade, as urbanized

communities began to engage in various

economic activities. Syria

during Early, Middle and Late Bronze Ages

(3100 - 1200 BC) When the earliest written records emerge in

the Early Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC), Syria shared in the

development of city states that arose in the

Sumerian lands to the east. Though of

different origins to the Sumerians, the

population of the mid-Euphrates city, Mari, based its social structure on

analogous systems. Literacy, through the

development of a system of cuneiform

writing, stimulated complex legal and

trading practices, the local monarchs' power

depending on the effectiveness of their

control of irrigation and trade. The rise of

the first truly imperial power in the

region, the Akkadian Empire (2340 -

2150), ended Mari's phase. Under the

subsequent rule of the

Dynasty of Ur, Mari retained a degree

of importance, while Ebla became a

subsidiary state. By 2100, the early experiments in urban

societies were disturbed by new population

movements that brought Amorite people

from the Syrian desert into the settled

lands of the Fertile Crescent. This period

of urban decay and disruption initially

brought an end to much of the pattern of

regional trade on which Ebla had thrived and

the city fell into decline. The Kingdom

of Yamkhad (Aleppo) became a major power

in this period, absorbing Ebla into its

orbit. Mari enjoyed some independence 19th - 18th centuries BC as an Amorite

city. The Babylonian leader to the

south, Hammurabi, ruled with reformist zeal

at home (he promulgated a codified system of

law in his name) but this did not distract

him from developing an appetite for

conquests which caused him to raze Mari

around 1759 BC. The Amorite Kingdoms of the

north managed to resist direct Babylonian

rule but traded extensively to the east. The next major change to the regional power

game came from the north west. The Hittites (Indo-Europeans by origin) had installed

themselves in central Anatolia and brought

an end to Babylonian power c1595 BC. A

non-Semitic people called the Hurrians had been moving into Syria in large numbers

from the north. A second analogous wave, the Mitanni people, soon arrived to blend

with the Hurrians to form a federation of

Hurrian principalities, the Kingdom of

Mittani (16th - 14th BC), centered on the present North East

Province around the Khabur River with links

to the "land of Ammuru" to the east. At about the 13th century to the south, the tribe of the

Israelites was moving into Palestine from

the east with consequences still to be

resolved 3000 years later. The Mediterranean

coast as a whole enjoyed a more prosperous

and untroubled life based on the sea trade

routes built up by the Phoenicians -

peoples of Semitic origin who had moved into

the region at the beginning of the second

millennium and had established a culture

that blended Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Aegean

and Egyptian influences. Syria

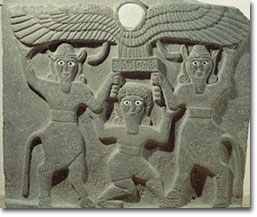

during Iron Age (1200 - 539 BC): Syria's ethnic and political chess board was

again scattered by the arrival of the Sea

Peoples around 1200. The Sea Peoples'

invasion brought an end to the apogee of Ugarit as well as to the Hittite Empire. Further

Semitic population movement arrived from the

south in the from of the Arameans, a

Bedouin people who concentrated particularly

in the north where around twenty so-called

"Neo-Hittite" principalities had arisen - Halab (Aleppo), Arpad,

Tell Barsib, Tell Halaf, Hattina and Hamath (Hama). The arrival of the

Arameans from the desert further scrambled

the mix. The art of northern Syria post 900

reflects this diversity of origins in a

clumsy attempt to rival the monumentality of

their Assyrian adversaries to the east. In the south, the

city-state of Aram-Damascus led a coalition

of forces that checked the ambitions of the

kingdoms of Israel and Judeah. On the coast,

the Phoenician cities survived the Dark Age

that followed the Sea Peoples' invasions and

continued to serve as a conduit for products

and ideas between Greece, Egypt and the

Asian mainland. The Assyrian Empire (1000 - 612 BC) took permanent control of

parts of northern Syria and Phoenicia from

853. The Assyrians pushed even more firmly

into Syria, ending Damascus' independence in

732. Even centers such as Arwad and Sidon could not escape the vehemence of the late

Assyrians' ambitions though Sidon resisted

even when Assurbanipal came down on it "like

a wolf on the fold" in 668. Eventually it

fell, not to the Assyrians, but in 587 to

Nebuchadnezzar, one of the first of the Chaldean rulers whose short-lived

dominance in Syria (605 - 539) followed

their defeat of the Assyrians after a long

period of rivalry in their common home

territory in Northern Mesopotamia.

Syria during Persian Period

(539 - 333 BC)

The Achaemenid Persians annexed much of

Syria as a consequence of their move

westwards and their defeat of the

Neo-Babylonians with the capture of Babylon

by Cyrus in 539. Syria was made their fifth

satrapy or province with its capital

possibly at Damascus. They recognized the

pervasive spread of the Arameans language

and its Neo-Phoenician script by adopting it

as the lingua franca of their empire,

ensuring its survival well into the Roman

period. The Persians brought a regular and

comparatively benevolent system of

administration to their 23 provinces but

above all the integration of the Syrian

coast into the network of exchanges across

the east Mediterranean to Greece heralded

the first of the great east/west clashes

that have focused on Syria. Syria

during Hellenistic Period (333 - 64 BC) This Greek-Persian contest was decided in

the great battles (the first at Issus in 333) in which Alexander the Great

defeated the forces of Darius III. Syria was

contested, with northern Syria falling to

Seleucos II Nicator after his victory over

Antigonus at the battle of Ipsus in

301. The south (including Damascus) and the

regions of Lebanon and Palestine were seized

by Ptolemy I Soter who had already been

given command of Egypt. The Seleucid Kingdom

began on an ordered and rational basis but

never succeeded in welding Syria into a

secure of the Macedonian dynasty. New

satrapal headquarters were established - Antioch, Seleucia (at the mouth of the Orontes in Turkey), Apamea, and Laodicea (Latakia)

were the major centers. Subsidiary centers

settled included Cyrrhus, Chalsis

ad Belum (Qinnesrin), Beroia (Aleppo), Arados (Arwad), Hierapolis (Membij), and Dura Europos, the two main Seleucid

domains, Syria and Mesopotamia. The

Ptolemies lost control of southern Syria by

198 BC when it fell to the Seleucid King,

Antiochos III Megas. This marked the

beginning of a temporary resurgence of the

Seleucid dynasty. By the beginning of the

first century BC, Seleucid Syria was fraying

badly at the edges with inroads by the

Armenians to the north, the Parthians to the

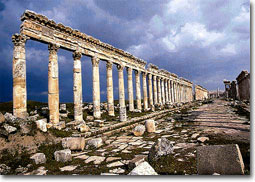

east and the Arab Nabateans to the south. Roman

Syria (64 BC - 395 AD): The Romans, who since their conquest of

Greece had shown interest in the fate of

Syria, became increasingly involved. In 64

BC, the Roman legate, Pompey, formally

abolished the Seleucid Kingdom and created

the Roman province of Syria with its

principle city (metropolis) at Antioch. For

a time, Syria became part of the setting for

the great leadership struggle that brought

an end to the Roman Republic. Antioch had

become the third imperial city after Rome

and Alexandria but other centers such as

Damascus, Beroia, and the trading hub of

Palmyra, also benefited greatly.

Economically, Syria flourished and became

not only an entrepot zone of central

importance in the east/west trade in

luxuries (from China, India and

Trans-Oxiana) but a major agricultural area

whose grain and wine supplied a good share

of the Roman market.

To service this

commerce, trade routes were systematized

through the building of roads, including the

north/south Via Maris and Via Nova

Traiana and the ease/west route through

Palmyra that saved considerable time and

effort over the northern route following the

Euphrates. Thus Damascus was given a more

monumental appearance through the provision

of a widened and arcaded axial thoroughfare

(later to be immortalized as the New

Testament as Straight Street) and a vastly

enhanced sacred precinct for the Temple of

Jupiter/Hadad (Damascus - Umayyad Mosque).

Other cities such as Apamea, Palmyra,

Laodicea-ad-Mare (Latakia), Canatha (Qanawat) and Bostra (Bosra) were

given similar treatment. The latter two were

re-planned by Trajan's more aggressive

policy of direct control resulted in the

annexation of the Hauran in 106 and the creation of the

province of Arabia. Rome regarded Syria as a

prized province and the position of legate

was a valued appointment.

By the late second century, the Parthian

wars were a dominant pre-occupation with

Parthia the only organized power able to

conduct a centralized campaign against the

Empire's might anywhere along its frontiers.

At this period, Palmyra had successfully

lived off its ability to act as a go-between

in trade across hostile frontiers. Palmyra

came under direct Roman rule and the sleepy

local garrison at remote Dura Europos on the mid-Euphrates was reinforced with

imperial forces. Successive Emperors over

four centuries were to pit themselves

against the Sasanian determination directly

to challenge Rome's presence. By the mid

third century, the situation of the east

frontiers of Syria was parlous, the low

points being the fall of Dura Europos in 256

and the capture in 260 of the Emperor

Valerian in person by Sasanian forces at Edessa, in spite of the presence of a

Roman force of 70,000. Christianity

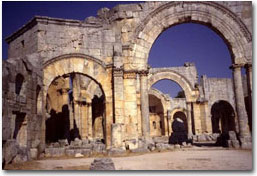

Christian liturgy in st.simon old churcheBy the time the Emperor Constantine gave official recognition to Christianity after 313, increasingly encouraging it as the state religion, Syria (and particularly Antioch) was already an area of intense Christian activity going back as far as the missions of St. Paul in the mid first century. Christianity with its blending of Jewish and Greek influences, was at first one more element, albeit a powerful one, in the Syrian melting pot. Before the Christianity became part of public life in the fourth century, churches were merely adopted dwelling places. After the official recognition of Christianity, they took on the form and scale of Roman public buildings. The pilgrimage phenomenon sponsored by Constantine's mother, St. Helen, with her visit to the holy sites of Jerusalem in 324 later proliferated in Syria, complemented by the arrival of the monastic tradition (from Egypt) and the veneration of places associated with ascetic and saintly figures. There are now countless major monastic villages and churches as pilgrimage centers such as Saint Simeon Stylites or Saint Sergius in northern Syria.

Syria in the Byzantine Era (395 - 636)

No area of the Mediterranean world contains such a wealth of evidence of this period as can be found in the many churches, village and monastic remains of Syria. The adoption of Byzantium as the second capital of the empire under Constantine foreshadowed the final transfer of the Roman capital to the East in 395, the start of the Byzantine era. The area of limestone west of Aleppo (5th - 7th century) continued to prosper, based on its olive oil exports; the Hauran was intensely exploited; the cities remained thriving. Church and monastic projects abounded and Syrian builders developed a repertoire of styles that adopted metropolitan and neo-classical models and blended them with elements from the east, often achieving a rather bizarre local mix whose remains are richly evident. The Sasanian Persians made increasing inroads into Syria, their destructive raids punctuated by a devastating series of earthquakes. In spite of the efforts of Justinian and later Emperors to stabilize the Eastern frontiers, by the early seventh century, Syria was virtually incapable of putting up serious resistance to the prolonged by Chosroes II who brought his presence in Antioch to a climax with the slaughter of 90,000 of inhabitants. The Byzantines had tried diplomacy under Maurice (r 582 - 602) but were subsequently divided by their leadership struggles. After centuries of warfare the Roman and Persian worlds had fought each other to standstill.

Syria during Arab Conquests (632 - 61)

Muhammad wanted to find new outlets to the north for the military, religious and commercial energies of the new Arab leadership. Few Syrian centers put up much resistance. Damascus surrendered twice, the second time in 636 after the crucial defeat of the Byzantine forces at Yarmuk. For almost two decades, the new leadership remained based in Medina and Southern Iraq. After Abu Bakr, the Caliphate passed to Umar (Caliph 634 - 44), Othman (Caliph 644 - 56), and then Ali (Caliph 656 - 61), the four comprising the group of Rashidun or "right-guided" Caliphs.

Umayyads (661 - 750):

Moawiya had taken the Caliphate and promptly decided to move the capital to Damascus (where he had built up his power base as Governor). The Umayyad Caliphate brought in what is perhaps one of the most fertile and inventive periods of Syrian history. The Umayyad embarked on the most confident period of their administration. This was marked by major building projects at home and expansion abroad, especially under Abd al-Malik (r 685 - 702) and his son al-Walid (r 705 - 15) who was responsible for the immense project of the new congregational mosque in Damascus (Umayyad Mosque) which 1200 years later still bears striking witness to the richness and variety of the Umayyads inspiration. Hisham (724 -43), another son of Abd al-Malik, was the last of the great Umayyad rulers. After him the Umayyad dynasty declined.

Abbasids (750 - 968):

A pretender, Abu al-Abbas, emerged in Iraq and marched on Damascus in 750. the Umayyads were eliminated, one grandson of Hisham fleeing to Spain where the Umayyad line survived for a further 500 years. The Abbasids transferred the Caliphate to Iraq (Kufa, until the founding of Baghdad in 762) and Syria became merely a neglected backwater, punished for its adherence to the corrupt and lax line of the Umayyads. Syria once again was contested from many directions. In this period of unparalleled confusion, the struggle for political dominance was matched by a resurgence of the Shi'ite/Sunni tensions as various factions fought to impose their views on an increasingly Islamicised population. Rebellions and disaffections abounded and many sects simply retreated to the mountainous and desert areas, there preserving a separate identity which is evident today in the country's ethnic and religious complexity. Syria's political history during this period can only be traced at the local level, separate lines of political succession being established in northern and southern Syria, depending on their degree of exposure to events in Egypt, Iraq, Byzantium and Turkey. Aleppo was controlled by the Hamdanid dynasty (944 - 1003) whose impetuous adventurism only served to make Aleppo a virtual protectorate of the Byzantines and later of the Fatimids. The Seljuq Turks who has extorted from the putative Abbasid Caliph a mandate to govern northern Syria effectively took over under Alp Arslan as Sultan (1070 - 2 ). Damascus, like Aleppo, experienced in the 9th to 11th centuries a time of anarchy, with a period of rule in the 9th century by the Cairo-based Ikhshidid dynasty. The continued rise of the Seljuqs brought the struggle for Syria to a new phase. They managed to take most of Syria including Damascus in 1075 and by 1078 were in Jerusalem. By the 11th century the Seljuqs were sufficiently strong in Syria to block the Fatimid dynasty's efforts to maintain control of Southern Syria.

The Crusaders:

After Pop Urban II (1088 - 99) made his stirring appeal to arms at the Council of Clermont-Ferrand in 1095, the Christian army that poured into Syria in 1097 found that the Seljuq leadership had disintegrated and that the land lacked any unified command for resistance. During the nine month siege which resulted in the brutal taking of Antioch, the armies divided following three leaders. Raymond, Count of Toulouse, set out for Jerusalem with what remained of the largely rabble army. Their taking en route of Maarat al-Numan produced another gross massacre but still there was no concerted Muslim resistance. From Maarat, the Crusaders marched south along the Orontes Valley and then turned towards the coast again through the Homs Gap, taking on the way the Kurdish fort which was to become the site of the great castle now known as the Krak des Chevaliers. It took sometime for the various Crusader princes to consolidate their hold on the Syrian coastal areas. The Crusaders' presence was seen as a straight invasion in which religion was a veil cast over territorial motives.

The Islamic Resurgence:

Aleppo was the first center for Muslim consolidation under the Zengid regents (Atabeqs), Zengi (1128 - 46) and his second son, Nur al-Din (1146 - 74), nominally subservient to the Seljuq Sultan of Mosul and through him to the Caliph in Baghdad. They destabilized the Crusader presence in the Orontes Valley. By 1154, they had brought Damascus under their control, uniting for the first time the resistance to the Crusaders in Syria into a single front and thus refining the concept of jihad. Nur al-Din completed the process, making serious inroads into the Crusader presence in the Syria coastal mountains but it was taken further by his nephew, Saladin. But Damascus, for long the frontline center of resistance to the Crusader presence in Jerusalem, was his forward base and there he initiated the line of Ayyubids (1176 - 1260 - after his family name) which later took the form of separate dynasties in Damascus and Cairo. From there he completed the unification of Syria, taking full control of Aleppo in 1183 and thus securing strategic depth for a vigorous campaign against the Crusader forces. Even Saladin's brilliant campaign in 1188, did not touch off a consolidated effort to dislodge them from the great fortresses at the Krak or Marqab or from the cities of Tartus, Latakia or Antioch. After Saladin died in 1193, the inspiration had gone. It took nine years before the Ayyubid lands came together again under his brother Aladil (Sultan in Damascus) 1196 - 1218.

The Mamelukes:

By the mid 13th century, the focus of the Muslim/Crusader struggle had moved to Egypt which became the target of the later Crusaders. The first of the Mongol invasions of Syria, under Hulaga, inspired the Mamelukes to rally the flagging forces of Islam (Battle of Ain Jalud on 3 September, 1260) and to take over Damascus from the last Ayyubid, al-Malik al-Nasr II. The ruthless leadership of the Mameluke Sultan, al-Malik al-Zaher Baibars (r 1260 - 77), gave renewed momentum to the anti-Crusader cause and the debilitated Christian presence was rapidly dislodged from Antioch and from the bastions at the Krak and nearby Safita. The process continued under Sulatn Qalaun (1280 - 90) who routed the remaining Crusader forces with their successive retreats from Marqab, Latakia, Tripoli and Tartus. The early Mameluke period was another golden age for Damascus that was made the second capital by the early 14th century. After 1380, a series of disastrous civil wars weakened the leadership and renewed threats of Bedouin and Tartar assaults. In the end, Mameluke rule collapsed as much from its unpopularity as from the swift inroads of a new Turkish incursion, this time in the form of the Ottoman military.

Ottomans (1516 - 1918):

The Ottoman Turks had already taken much of Asia Minor before they moved in on Syria. In 1516, the Mameluke garrison quietly slipped out of Damascus to allow the new Sultan to make his entrance. Shortly after, under the long reign of Suleiman (1520 - 66), the administration of Syria was systematized, its population counted and its revenues stabilized. The early Ottoman period (16th to 17th centuries) brought a new impetus to the development of the three Syrian provinces, Aleppo, Damascus and Raqqa. The role played by the Syrian provinces in the administration and provisioning of the annual pilgrimage /haj/ to Mecca did much to advance the economy and external trade grew. Aleppo became the base for a substantial foreign trading presence, a role that Damascus shared only to a limited extent. The 19th century was again a troubled period for Syria. Ibrahim Pasha was forced out in 1840 and Ottoman rule uneasily restored in 1860, partly as a result of the Druze/Christian troubles in Lebanon, a terrible massacre broke out in Damascus after a Muslim attack on the Christian quarter. In 1914, Damascus was made the general headquarters of German and Turkish forces in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. World War I was a time of extreme privation in Syria and Lebanon with Turkish indifference and maladministration aggravating the effects of food shortages, leading to starvation and serious epidemics.

French Mandate:

Allied forces entered Damascus on 1 October 1918; the city has been abandoned the day before by its Turkish garrisons. Elections to a National Syrian Government the next year and the appointment of Feisal as King cut across British and French ambitions and were overturned by the establishment under the provisions of the Versailles Conference of a French mandate in Syria. The mandate was imposed by force of arms in 1920 and was accepted at best grudgingly thereafter but not for long, France faced a hostile population and wearying resistance in 1925, a serious revolt broke out in the Hauran and spread to Damascus where the French restored to the first mass bombardment of the city. The mandate formally ended in April 1945 with Syria's admission to the United Nations, though that outcome did not constrain French forces from a final bombardment of Damascus the next month. French forces finally withdrew in late 1946.

The National Bloc signing the Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence in Paris in 1936. From left to right: Saadallah al-Jabiri, Jamil Mardam Bey, Hashim al-Atassi (signing), and French Prime Minister Léon Blum.

|