|

140 km

south east of Deir Ezzor, 12 km west-north west of Abu Kemal on

Syria/Iraq border, on the Euphrates; lies a site of a central

importance, Mari, "a unique example of a Bronze Age palace" giving "an

exceptionally concentrated picture of Syro-Mesopotamian world in the

words" of its current excavator, Jean-Claude Margueron. The finds in

Mari have given large contributions to the unraveling of the history of

Syria/Mesopotamia region during the early millennia of recorded

history. Its excavation rested for many years in the hands of the

French archaeologist, Andre Parrot, who supervised the excavations from

1933 to 1974; a remarkable record. Since 1978, excavations have

continued under Margueron with the aim of embracing Mari's role in the

wider Euphrates valley. 140 km

south east of Deir Ezzor, 12 km west-north west of Abu Kemal on

Syria/Iraq border, on the Euphrates; lies a site of a central

importance, Mari, "a unique example of a Bronze Age palace" giving "an

exceptionally concentrated picture of Syro-Mesopotamian world in the

words" of its current excavator, Jean-Claude Margueron. The finds in

Mari have given large contributions to the unraveling of the history of

Syria/Mesopotamia region during the early millennia of recorded

history. Its excavation rested for many years in the hands of the

French archaeologist, Andre Parrot, who supervised the excavations from

1933 to 1974; a remarkable record. Since 1978, excavations have

continued under Margueron with the aim of embracing Mari's role in the

wider Euphrates valley.

Mari was the 3rd millennium BC royal city-state par excellence. It

controlled access between central and southern Mesopotamia and the

drier plains of northern Syria and the upper Euphrates/Khabur system.

Caravan routes through Mari also brought tin for the bronze industries

to the west. Its key position between the confluence of the Khabur and

Euphrates and the cliffs further south at Baghuz explain its choice as

the site for a new city built by political decision. Mari

was first occupied at the beginning of the third millennium (2900 BC).

Positioned in an area of limited natural agricultural potential, the

center based its foundation not only on its trading position but on a

sophisticated irrigation scheme. It was surrounded by a circular

rampart and ditch (1.9 km in diameter) through which was dug a canal

for the dual purpose of water supply and controlling navigation on the

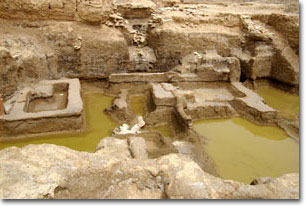

river. The late excavations led to development of canals in Mari,

including a 120 km navigation link between the Khabur and Euphrates

rivers.

The first major period of development (2700 - 2600 BC) saw the

construction of a great palace, the temple of Ishtar, Nini-Zaza,

Shamash and the terrace area or "Massif Rouge". Mari succumbed to the

Akkadian Empire for a while but re-established its prosperity, its

population heavily boosted by the arrival c2000 BC of many Amorites.

Mari lost out in the power struggle touched off by the rising dynasty

of Babylon. Occupied for a time by the Amorite leader Shamsi-Adad (1813

- 1782 BC), it briefly found its independence under Zimri-Lim (1775 -

60 BC) only to lose it to Hammurabi of Babylon (c1792 - 50) in 1760.

Its walls were razed, its temples sacked and the palace of Zimri-Lim

set on fire and dismantled. The city was no longer a center of any

importance from that time though there are signs of limited

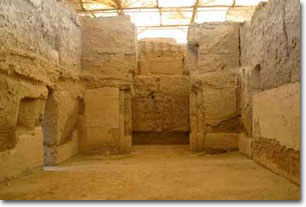

re-occupation in the Seleucid and Parthian periods. The largely mud-brick remains which have been successfully peeled of to

expose the preceding layers beneath are difficult to appreciate. Zimri-Lim palace: It is the most extensive excavated in the Middle East and was

constructed across several centuries. It has 275 rooms covering 2.5 ha.

There is a variety of finds in the palace well preserved including the

notable statues of Ishtup-Ilum (Governor of Mari) and of a water

goddess and an archive of 15000 tablets recording the household

accounts of the palace as well as diplomatic and administrative records

of the kingdom. The main gateway to the palace of Zimri-Lim was on the north eastern

side of the roughly square palace compound which was originally

surrounded by a mud-brick rampart. Many of the rooms were decorated

with wall paintings, partly preserved in the Aleppo and Damascus

Museums as well as in the Louvre. The Religious Buildings: There are also a number of religious buildings around the palace,

including the Temple of Lions (c2000 BC) and that of Shamash. In the

Temple of Ninni-Zaza (mid third millennium BC) was discovered a

remarkably rich trove of statues including that of the singer

Ur-Nanshe. Temple of Ishtar (3rd millennium) is typical of Mari in its layout; they're all very important to inspect. |